On 30 July 1941 in London, Poland and the Soviet Union concluded a treaty, supplemented by a military agreement on 14 August of the same year, which resulted in the creation of the Polish Armed Forces in the Soviet Union. The army was not to exceed 30,000 soldiers in two divisions.

For thousands of Polish citizens scattered across the vast territory of the Soviet Union, this meant a not easily realised, but a real possibility of leaving the prisons and gulags in which they were imprisoned as a result of Soviet mass deportations in the inter-war period and after the Soviets invaded Poland in 1939. They arrived at the recruitment points, travelling hundreds of kilometres, often on foot – men as well as women and children, hoping to help the nascent Polish army. Its commander was General Władysław Anders (1892-1970), released by the Soviets from the prison to which he had been sent after the September 1939 campaign. He quickly won the trust of his subordinates and the Polish civilian population.

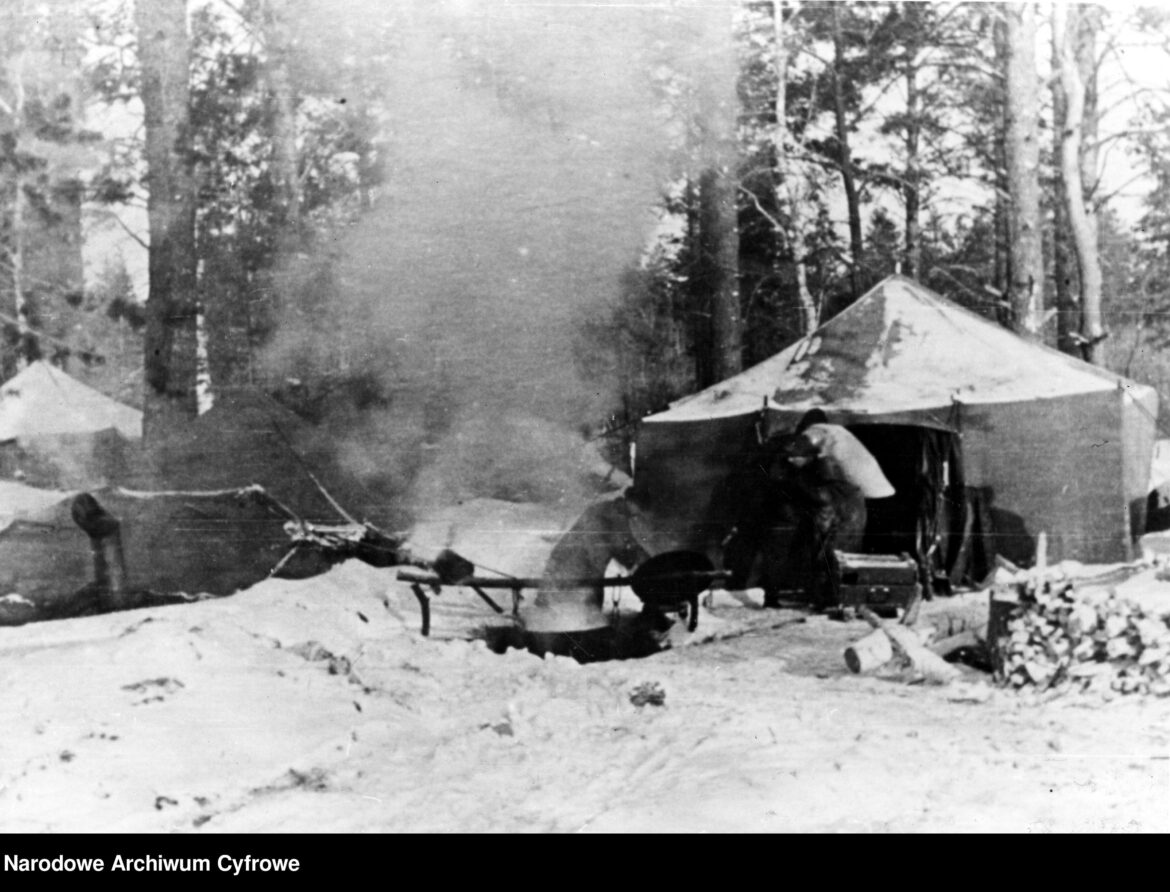

The army was not provided with equipment, clothing, accommodation, adequate food or medicine. The Soviet side insisted on sending completely unprepared troops to the front; eventually it banned further recruitment of soldiers. In this situation, Anders began to push for the evacuation of Poles to Iran. Decisions on this were extremely difficult. Each day of delay, on the one hand, increased the chances of those who had not yet managed to reach the relocating recruiting points; on the other, it exacerbated the risk that the army would not be released from the USSR.

In the end, some 80,000 soldiers and 40,000 civilians were evacuated from the Soviet Union between the spring and autumn of 1942. The soldiers themselves decided to share rations with the civilian population. Once the army was in the Middle East, Anders made the completely unusual (expressed in a secret order to the gendarmerie) decision not to prosecute deserters. This concerned Jews (some 2,500 in all) who had fled to Palestine. Among them was the future Prime Minister of Israel Menachem Begin. In addition, as a result of the efforts of Jewish organisations, some 1,200 to 1,600 Jewish civilians, mainly children, left for the territory of the future Israeli state.