There have been few figures like Jan Szczepanik in the history of European civilisation. He is the “Renaissance man” of recent times. His inventions were the prelude to colour photography and television. Some of them, like the bullet-proof waistcoat, saved lives.

Born on 13 June 1872, Jan Szczepanik, often referred to as the “Polish Edison”, began his life’s journey in humble conditions. His mother, Marianna Szczepanik, died unexpectedly shortly after his birth, leaving him in the care of his aunt, Salomea Gradowiczowa, and her husband Wawrzyniec, an employee of the Krosno municipality. He lived in Poland, which was then under Austrian occupation. It should be remembered that in the 18th century, the three neighbouring powers (Russia, Prussia and Austria) seized Poland by force, led to the liquidation of Polish statehood, and that the Poles regained their freedom in 1918.

Interrupted education

From an early age, Szczepanik showed brightness of mind and curiosity about the world around him. He started his education at a school in Krosno and then continued at a secondary school in Jasło. Although he had very good achievements in mathematics and natural sciences, he encountered difficulties with classical languages, which eventually led to him dropping out of middle school in his fourth year. However, due to his potential, the school management allowed him to change school facilities.

Szczepanik moved to Kraków, where he graduated from the Teachers’ Seminar in 1892. As a teacher, he worked at schools in Potok, Lubatówka and Korczyna, where he gained a reputation as an innovator, often involving students in practical projects and experiments instead of traditional lessons. It was during this period that he began to take an interest in colour photography and innovations in weaving.

Teaching was only an introduction

In 1896, Szczepanik decided to leave the teaching profession and move to Krakow, where he focused on technical experiments in a rented flat.

In Krakow, with the support of the local Weavers’ Society, he began working in a photographic shop. There he met Ludwik Kleinberg, who, noticing his extraordinary abilities, became his patron. In 1898, Szczepanik went to Vienna, where he founded the company Société des Inventions Jan Szczepanik & Cie together with Kleinberg and Franz Habrich, which enabled him to devote himself fully to his invention activities.

In the Austro-Hungarian capital, Szczepanik quickly gained recognition, and his innovations in weaving, optics and electronics attracted press attention. Between 1896 and 1906, he registered numerous patents relating to the textile industry, including a weaving system involving automated stencil production, novel methods for jacquard machines and techniques for producing multicoloured decorative fabrics. His invention of light-sensitive fabric, used in the production of tapestries by the photographic method, revolutionised this market.

Szczepanik’s inventions save lives

Szczepanik was also the inventor of the bullet-proof waistcoat, known as the ‘Szczepanik armour’, which saved the life of Spanish King Alfonso XIII in 1901. In gratitude for this achievement, the king awarded him the Order of Isabella the Catholic. Szczepanik also gained the recognition of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, who invited him to St Petersburg and presented him with a gold watch with diamonds and a brooch for his fiancée.

His work on the telectroscope, a precursor to television, also received international recognition. The first public demonstration of the device took place in Vienna, and its improved version, the telephot, was presented at the 1900 World Exhibition in Paris.

Szczepanik was a versatile inventor whose work influenced the development of colour photography, colour film, television, sound film and telecommunications. His inventions, such as the photosculptor and the self-contained draught regulator, testify to the extraordinary creativity and technical skill of this experimenter. In 1899, he created colour small-image film, whose discoveries were later used by Kodak and Agfa.

The inventor’s work and the military

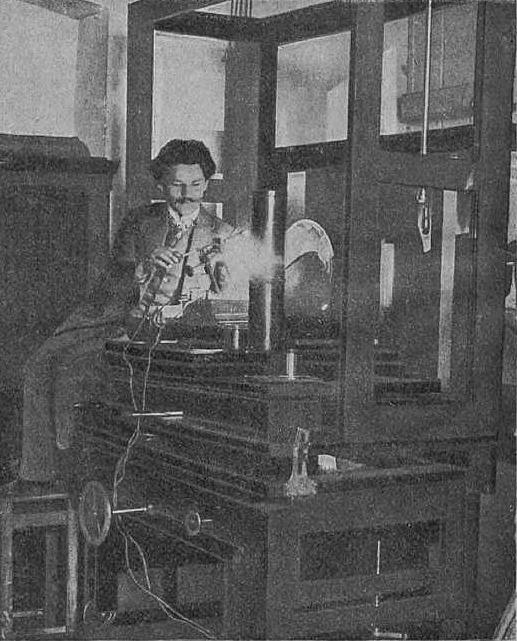

The years 1898-1902 were a period of intense work and creativity for Szczepanik. His studio in Vienna became a meeting place for many European industrialists, and his achievements were widely commented on and appreciated in both the scientific and literary worlds, as evidenced by visits to his studio by Gabriela Zapolska and Mark Twain. The Pole’s achievements in the invention were recognised around the world, including in the United States and China.

Despite his fame and recognition, Jan Szczepanik was called up by the Austrians for military service in 1901, which led him to the fortress of Przemyśl. Here, an important strategic point for the Habsburg monarchy, Szczepanik had the opportunity to work on innovations such as the spark telephone and the automatic rifle. However, his stay in Przemyśl was not limited to scientific work; he actively participated in the life of the city, where he met his future wife, Wanda Dzikowska. In 1902, the couple married in Tarnów.

Between Tarnów and Berlin

After the wedding, Szczepanik moved to Tarnów, taking up residence in his father-in-law’s tenement at 11 Chopin St. There, despite earlier financial problems and the bankruptcy of his company, he resumed his inventive activities with the support of his family, focusing on the development of colour photography.

Szczepanik was an avid lover of science and had an extensive library. He was also passionate about mountain hiking. Despite his achievements, he remained a modest person, paying little attention to the outward signs of wealth that his innovative ideas brought him.

After the end of the First World War in 1918. Szczepanik divided his time between Tarnow and Berlin, where he continued his research. Sadly, his life was cut short by his premature death in 1926 from cancer. He left behind an impressive legacy in technology, confirmed by numerous patents.