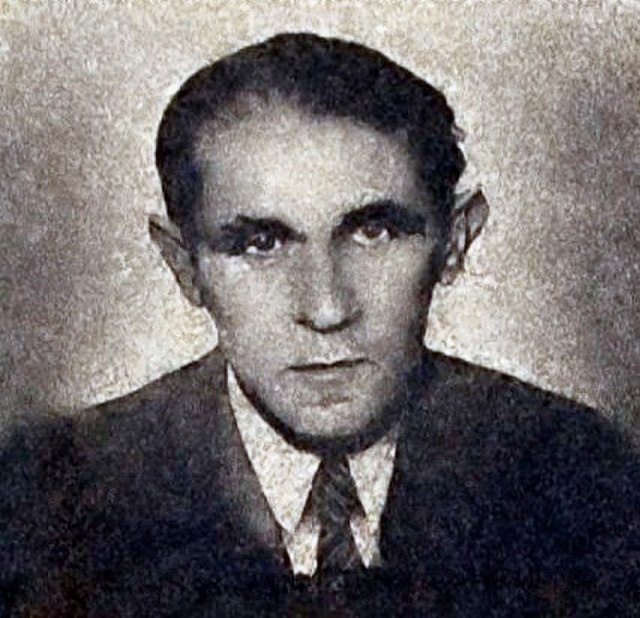

Bruno Schulz (1892-1942) – a versatile writer, graphic artist, painter and literary critic was proclaimed the symbol of 2022 by the Senate of the Republic of Poland. This decision will commemorate the upcoming 130th anniversary of the artist’s birth and the 80th anniversary of his tragic death in German-occupied Drohobych.

Today, the knowledge of Schulz’s work goes far beyond Israel, Poland and Ukraine, and his stories have been translated into 45 languages, including recently Chinese, Turkish, Estonian, Albanian, Greek and Vietnamese. Although he was the author of only two collections of short stories (Cinnamon Shops and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass) and a number of separate essays and reviews, their literary value is regarded very highly, inspiring worldwide admiration, despite a small legacy in terms of volume.

Bruno Schulz, a Jew from the Polish town of Drohobych, now in Ukraine, is called “the master of the Polish word”, as says the memorial plaque on his house. Brought up in the cult of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, and at the same time assimilated with Polish culture and involved in the activities of the cultural community of the Second Polish Republic Bruno belonged to the Jewish intelligentsia from the Lvov Region.

Schulz was one of the best students at the Franz Joseph I Drohobych State gymnasium. Ended his education with his gymnasium diploma with honors in 1910, he decided to study Architecture at the Lvov Polytechnic University. During his studies, he became seriously ill with heart and lung issues and had to interrupt the course and return to Drohobych. From 1918, the writer belonged to the local Jewish-Polish group of authors “Kalleia” (“Beautiful Things”), which gathered intelligentsia interested in art. Reading a lot, mainly fiction and books on exact sciences – physics and mathematics, Bruno Schulz was self-taught. He also made graphics using a rarely used cliché-verre technique.

He spent most of his life in the beloved Drohobych, recorded in the pages of his stories, sketches and paintings. He made several trips to Germany, Paris, a stay in Vienna, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, and visits European art museums, which resulted in an excellent knowledge of the works of great old masters, such as Albrecht Dürer, Titian, Correggio, Claude Lorrain, Diego Velazquez and Rembrandt. Features inspired by the works of baroque and classicist masters, but also nineteenth-century artists such as Francisco Goya, can be found in Schulz’s artworks and in the poetic, beautiful descriptions of interiors, nature and other elements of the world, which he portrayed in his stories. Having broad European horizons, Schulz maintained contacts with the famous German writer Thomas Mann and representatives of the avant-garde of Polish literature, including Witold Gombrowicz (1904-1969), Stanisław Ignacy Witkacy (1885-1939) and Zofia Nałkowska (1884-1954), but he did not receive much recognition during his lifetime, mainly because of his shyness and hidden personality.

Many people ask themselves what is the phenomenon of Schulz’s work. Tomasz Wójcik, a prominent expert, noted that there is “a glaring disproportion between the volume of his work and its semantic, ideological, and philosophical capacity. It simply hides a huge cognitive potential, surprisingly, still inexhaustible.”

The language of Schulz’s prose is also characteristic: incredibly rich, poetic, full of archaisms as if rediscovering the original meaning of words. The stories presented in his stories follow the mythical order and have universal features. Although he spent most of his life in provincial Drohobych, Schulz created his immediate surroundings, his family and his hometown as a kind of universe. Using the original technique of reality mythization, through his extraordinary imagination he raised this small quotidian world to the rank of the center of the world where extraordinary, fantastic and momentous events were to take place.

“Legend is an organ of grasping greatness, it is a reaction of the human spirit to greatness. When it comes to people of ordinary measure and ordinary events, psychology, pragmatism, realistic methods of history suffice. With this key, we open everyday life and many believe that it opens everything” – says Schulz in his essay from 1935, written in honor of the Marshal of Poland Józef Piłsudski (1865-1935).

Schulz, like the character of Flâneur from Walter Benjamin’s “Passages”, walked the streets not only of his provincial shtetl, but of the entire monumental European culture. Inspired by ancient culture and art, the son of a Jewish textile merchant and an extraordinary erudite, he found an escape from the monotonous everyday life of the town and family financial troubles after the death of his father, Jakub Schulz, and brother, Izydor Schulz. He created a stronghold of a culture that was not obsolete, but an ever-living, fascinating treasury of individual and collective memory, based not only on Jewish tradition but also on European heritage and art.

The outbreak of the Second World War did not interrupt Schulz’s creativity. Probably then, i.e. around 1941 he completed his lost novel “Messiah”. In July of that year, when the troops of the Third Reich entered Drohobych again, the German occupants quickly began to repress and persecute Jews. They were forced into slave labor, their property was confiscated, and mass murders began in the surrounding forests. Germans established a ghetto where Schulz’s family was imprisoned. Schulz himself lost his job at the school because all school facilities were closed. In order to survive, he found a job as an organizer of the book collections stolen by Germans. He was also, as an artistically gifted person, “under the care” of Felix Landau, a Gestapo officer who personally participated in the mass executions of Jews. In exchange for the alleged protection, Landau used Schulz’s artistic talents to decorate the walls of the children’s room in his villa with fairy-tale compositions or decorate the interior of the Gestapo casino. The artist was useful to Landau, but he couldn’t feel safe as the terror raged all-around – many of the writer’s friends and acquaintances died at the hands of the Germans. Schulz feared for his life and his family, planning his escape from the ghetto.

His Jewish and Polish friends tried to help him. The Polish authors, including the writer Zofia Nałkowska, organized false documents for him, enabling him to escape from Drohobych and hide in Warsaw. On November 19, 1942, he was supposed to go to Warsaw but he did not make it. He died shortly before the planned departure, shot by a German officer about 100 meters from his first family home in the Market Square. It is believed that the writer’s body was placed in a common grave, which could not be found after the war. After the Second World War, during the times of the Soviet Union, the Jewish cemetery was annihilated and apartment blocks were erected there.

The work of Bruno Schulz is a manifestation of the extraordinary multiculturalism of Poland, where the Jewish community played a significant and historical role in culture, drawing inspiration not only from the Jewish tradition but also from Polish culture and European heritage. The memory of Szulc and his works is cultivated. Since 2001, the Yad Vashem Institute has housed most of its frescoes, which the employees of this institution carefully cut from the walls of Landau’s villa in Drohobych. The remains of the frescoes left on the site were transferred to the museum in Drohobych. It is also worth making a trip to Drohobych, where the International Bruno Schulz Festival has been held every two years since 2004 (http://www.brunoschulzfestival.org ). Despite 80 years passing since Schulz’s death, Drohobych still retains its extraordinary charm, atmosphere and appearance of old houses, synagogues and gardens from Schulz’s times, which makes fans of his work feel there as if they moved to the pre-war world of the writer and artist.