Thanks to Marek Grechuta’s unforgettable music arrangement, the bass-booming ‘bittern bumblebee” became known to most of Poles, especially amongst the older generation. The song was included in an album released in 1984, and its lyrics come from Bolesław Leśmian’s volume of poetry titled Meadow, published in 1920.

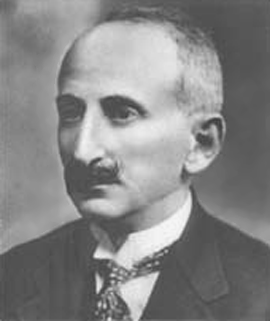

Bolesław Leśmian (1877?-1937), Jan Brzechwa (1898-1966) and Julian Tuwim (1894-1953) are among the most recognisable Polish poets. Like several other writers recorded in the history of 20th-century Polish literature, they were of Jewish origin.

The first two mentioned were cousin brothers who were born into the polonised Lesman family. Both were lawyers by profession, but their passion was Polish literature. Bolesław Lesman’s mother, Esther (née Sunderland) (she also used the name Emma), was the daughter of a factory owner, while his father, Isaac Lesman, like his ancestors, was a bookseller. In 1887 Isaac converted to Catholicism, taking the name Joseph. This was another step demonstrating the assimilation of this family.

At his father’s pressure, Bolesław was educated in Kijów (now Kyiv), where he graduated in law. After studies, he travelled abroad, which was a common habit in wealthy families. After the First World War, he worked as a legal trustee in Hrubieszów and then as a notary in Zamość. He disliked this work and in practice left it to the people employed in the office, which was not without consequences: one of the employees embezzled a considerable sum of money. Bolesław Lesman devoted himself entirely to poetry, even changing his surname to make it resound with a typically Polish softened pronunciation. Between the two world wars, he published four volumes of poems, and their subject earned him the name The Green Regular. He also wrote fairy tales, essays, translated Edgar Allan Poe, and wrote in Russian.

Another Polish poet Jarosław Marek Rymkiewicz (1935-2022) claimed that Bolesław Leśmian was one of the most underrated authors, who should be placed alongside Jan Kochanowski, Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki. The language used by Bolesław Leśmian was so innovative that in order to describe it, theoreticians of Polish language created a new concept – lesmanisms. These are specific neologisms, mostly used to denote what is absent or negligible: thus, we have mourninglessness, unintelligibility, incomprehensibility, we can unbreathe, idlenessize, wondering what to do with destructionness. According to J.M. Rymkiewicz, through jealousy or misunderstanding, Bolesław Leśmian was rejected by his contemporary poets, not allowed to join the elite group of poets who sat at the famous table of the Skamandrites on the mezzanine floor of Warsaw’s “Ziemiańska” café. This caused the author to become bitter and close in on himself.

Privately, Bolesław Leśmian was not an easy man to live with. He squandered money, had a predilection for gambling and was notorious for his love affairs, from which his wife and two daughters suffered.

Leśmian died of a heart attack and was buried in the Powazki cemetery. His work is an inspiration for many musicians, apart from Marek Grechuta, songs to his words have been performed by Grzegorz Turnau, Magda Umer, Czesław Niemen, the Old Good Marriage and others.

To some extent, Polish literature owes Bolesław Leśmian the fact that his cousin took up the pen. Here, Jan Wiktor Lesman, or Jan Brzechwa – a children’s author known to all Poles should be mentioned. It was Bolesław who came up with this nickname, intended to evoke an arrow symbol (brzechwa being its central, wooden part).

Julian Tuwim, who in the interwar period was recognised in “Literature News” as the most independent man in Poland, and after World War II agreed to changes suggested by the communist authorities to the poem “Polish Flowers”, which he had been writing since 1940, also wrote for children.

Artistically, he belonged to the already mentioned, elite group of Skamandrites, but he also happened to create in the competitive current, called the city-mass-machine (for example, the famous poem “Locomotive”).

Tuwim was born in Łódź, to an assimilated Jewish family. He spent the entire interwar period in Warsaw, where he left his hometown to study law and Polish studies, which he quickly abandoned. He worked as a lyricist (e.g. song “Love will forgive all”, programmes of the Sphinx theatre), journalist, poet and essayist. During the Polish-Soviet War, he was employed in the press office of Józef Piłsudski.

As he often emphasised, he considered himself a Pole. Because of this declaration, he experienced incomprehension and rejection by part of the Jewish community, while on the other hand his Polishness was sometimes ridiculed. He was also accused of scandalising, encouraging desertion from the army (the poem To a simple man, 1929), defaming authorities (The ball in the opera , 1936), and so on.

Fleeing the German occupation, Julian Tuwim left for France in 1939, from there to South America, then to New York. Deeply experiencing the annihilation of the Jews and sympathising with the victims, in 1944 he wrote the manifesto “We, the Jews of Poland”. After the Second World War, he decided to return to Poland, which led to conflict and the breaking of contacts with his long-standing friends who had remained in exile.

Julian Tuwim’s return was regarded by the people’s authorities as a propaganda success. The poet was provided with luxurious conditions for those times. He did not shy away from laudations in honour of Joseph Stalin.

Julian Tuwim’s funeral was very solemn. He was buried in the Military Cemetery in Warsaw’s Powazki cemetery.