Today is the 105th anniversary of the restoration of Poland’s independence, heralded by the Provisional People’s Government of the Polish Republic, which was formed at the beginning of November 1918 in Lublin. Although it only functioned for a few days, undoubtedly it was an important element in the process of the Polish nation’s striving for self-determination, and its programme fundamentally changed the perception of the hitherto socio-political system.

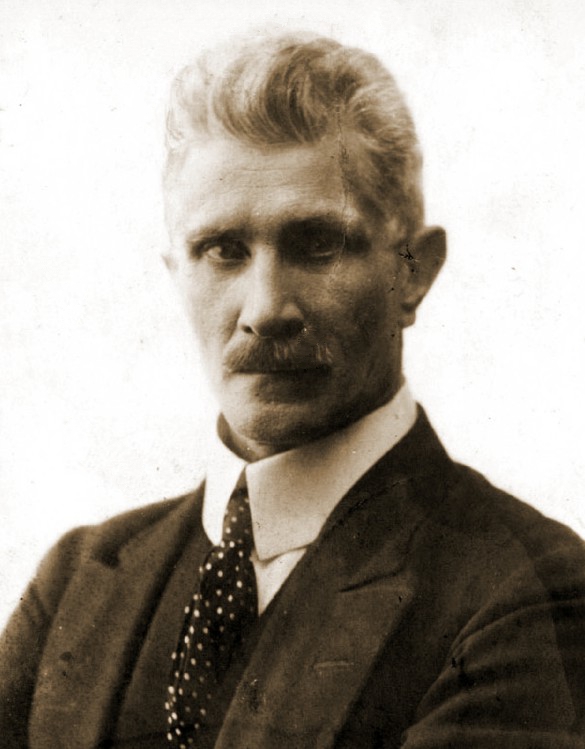

The resurgent Polish state had to face several social problems that resulted from the 123-year period of partition. The country had been devastated by more than four years of warfare, and poverty was widespread. At this crucial time, the left-wing independence movements concluded that efforts should be made to form a workers’ and peasants’ government, and so on the night of 6-7 November 1918, a “Manifesto” was posted on the walls of Lublin, announcing the formation of the Provisional People’s Government of the Polish Republic, with Prime Minister Ignacy Ewaryst Daszyński at its head.

The “Manifesto” of the People’s Government itself was at the same time a political programme containing a vision of a new system of democratic Poland. It can be described as the most mature project for the reconstruction of social relations, addressed to the Polish people, workers, peasants, and soldiers. The text reads: “Polish people! Polish peasants and workers! If you want to take your rightful place in the family of free nations, if you want to be the host of your own land, then you must take power in Poland into your own hands, you must build the edifice of the Independent and United People’s Republic of Poland yourself”.

The members of the government, drawn mainly from the Polish Socialist Party, the Polish Social-Democratic Party or the Polish People’s Party “Liberation”, proclaimed a Polish People’s Republic, encompassing areas inhabited by Poles, with its own maritime coast. Its first president was to be elected by the Legislative Sejm. In addition, it was an innovative idea in Europe to grant active and passive suffrage to all citizens, without distinction of sex, who had reached the age of 21, which soon became an unquestionable foundation of democracy.

The Manifesto then declared the political and civic equality of all citizens regardless of origin, nationality, or religion. Freedom of conscience, speech, press, the right to assemblies, marches, and associations were guaranteed, and the possibility of forming trade unions and organising strikes was also permitted. A reorganisation of the country’s administration in a democratic spirit and the establishment of a People’s Militia to maintain security were planned and a decision was taken to provide the population with the most necessary foodstuffs, which was the government’s most difficult and pressing endeavour.

The issue of donations and majorates was also addressed, recognising them as state property, as well as private and former government forests. Social issues were not neglected either, announcing the introduction of an eight-hour working day, be it in industry, crafts, or commerce. The first projects of a pro-social nature to be voted on in the future Legislative Assembly were also preliminarily identified, including: the expropriation and abolition of large and medium landholdings, the nationalisation of mines, salinas, the oil industry and communication routes. In addition, it called for the social status of workers to be raised by allowing them to participate in the administration of those industrial plants which, for various reasons, would not be nationalised immediately. It was also announced that a new law would be created to allow for the confiscation of assets created during the war through speculation in commodities.

In addition to the will to introduce the aforementioned eight-hour working day, announcements of the creation of laws on labour protection, unemployment, sickness and old age insurance, and the introduction of universal, compulsory and free schooling were essential for the general public. For this reason, the inhabitants of Lublin participated en masse in political rallies, expressing their support for Daszyński’s cabinet. Importantly, despite the fundamental, uncompromising content of the Manifesto, it should be noted that the socialists were aiming to level out social inequalities, at the same time firmly condemning the Bolshevik methods of implementing reforms.

It was already on 10 November 1918 when Józef Piłsudski returned from Magdeburg. Daszyński finally submitted to Piłsudski’s will, which demanded the formation of a national government composed of representatives of all political groupings. Accordingly, on 17 November 1918, the Provisional People’s Government of the Republic of Poland in Lublin, led by Stanisław Thugutt, terminated its activities by issuing two more decrees: “Decree on the eight-hour working day” and establishing “Minimum service conditions for the lower rural service”.

Contemporary historians believe that the People’s Government was an episode in the process of restoring Poland’s independence. However, as the first Polish government fully independent of the partitioners, it quickly developed a coherent and modern political programme that addressed many important social issues. The next Cabinet, led by Prime Minister Jędrzej Moraczewski, committed to implementing its fundamental assumptions.