In the Second Polish Republic, the educational institution, which was commonly referred to as the Father Boduen Home, was a self-governing institution run by the Warsaw municipal board to give a shelter for mothers and children. During the war, Jewish children were among its residents. The home has existed continuously since the 18th century.

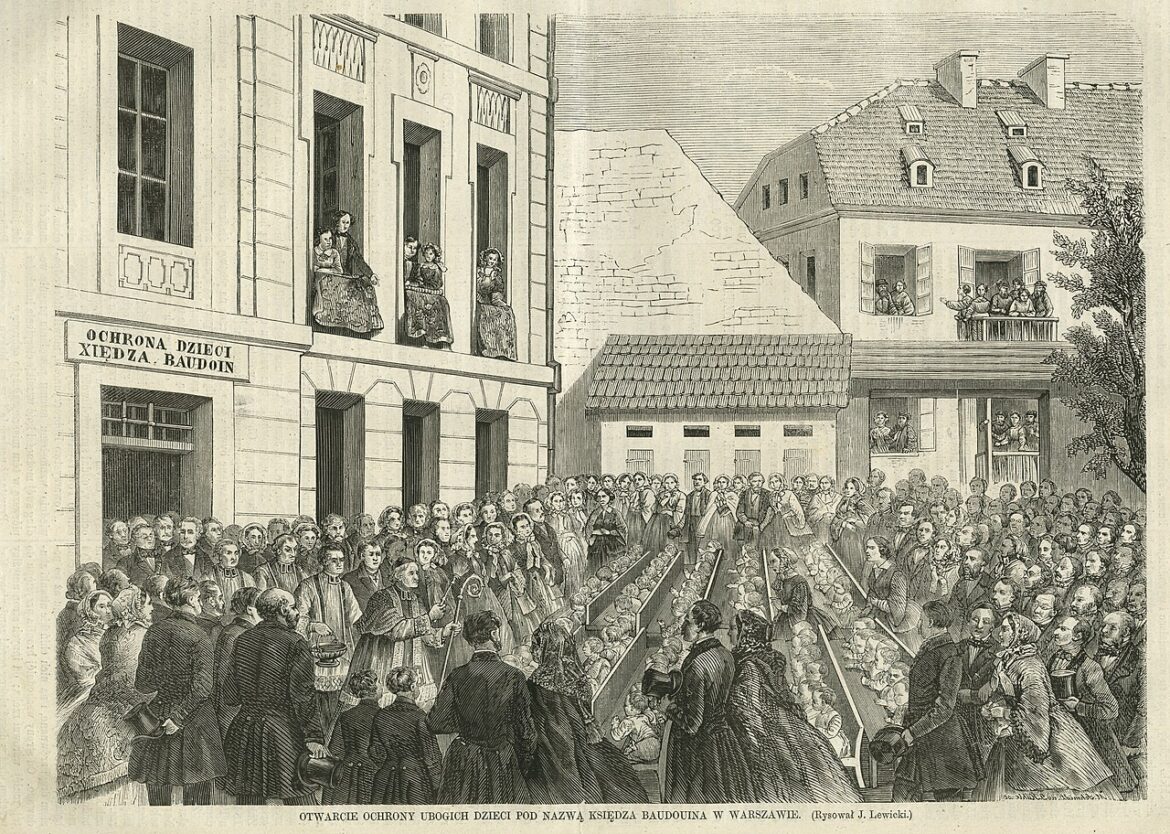

The institution is considered to be the first orphanage in Poland. It was founded around 1732 by Father Gabriel Baudouin. The French Catholic presbyter represented the Congregation of Missionary Fathers.

Residents of Warsaw knew that an opening with a tray was installed in the gate of the building. When you pulled the string, the tray slid out of the gate and then you could leave the baby in it. When, with the help of the string, the tray disappeared into the gate, a bell rang to alert the House staff. This meant that a new ward arrived.

In 1838, the orphanage passed into secular hands, and it was subordinate to The General Medical Council, the Warsaw Charity Society or the Main Welfare Council and finally the Municipal Council of Public Charity, and then, during the Second Republic, the Warsaw City Board.

After Poland was occupied by the Germans in 1939, the institution had to face the anti-Jewish policies of the occupiers. Its staff rescued Jewish children from the Holocaust. These wards, who were characterised by their distinctively Semitic appearance, were taken to the suburban provinces of Warsaw – to Klarysewo, Góra Kalwaria, Ignacow, Otwock and Pruszkow, where there were nursing homes. Some children travelled a little further, for example to Turkowice. There, an orphanage was run by the Servant Sisters of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The director of the Home during the war was Maria Prokopowicz-Wierzbowska, a doctor who temporarily housed Ludwik and Hanna Hirszfeld and others during the war. To save Jewish children, she cooperated with Jan Dobraczyński, who was the head of the Closed Care Section of the Warsaw Department of Care and Health in the Warsaw City Board. Those two, as well as several other people at the institution who were involved in the campaign to save Jewish children, had to remain strictly undercover. Children admitted to the institution had to have “Aryan documents” because the Germans systematically carried out inspections at the Home, looking for Jewish wards.

Over time, the number of collaborators expanded, including Irena Sendler. The exact number of children who were rescued is not known. There were probably around 200.